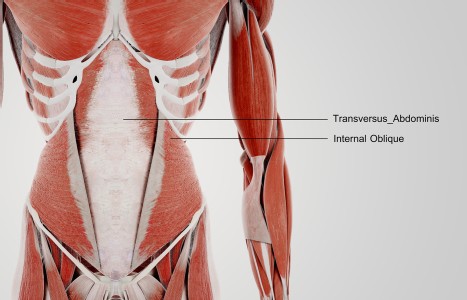

TrA-2, my primary needle location, I needle 95% of the time and I think it works the best. You’ll know you have the right point location when you discover the muscle twitching when applying electric stimulation.

History Repeats Itself: Excavating the Company Colon

"Tell the doctor what you feel," says the parent. The child, seated on the examination table, shrugs and remains silent.

"Go ahead," urges the mother. "Tell him what you told me." The shirtless child squirms and mumbles something unintelligible. He is nervous about describing his discomfort to an authority figure in a starched white coat. The doctor, though seemingly concerned, is short for time and wants quick resolution.

"If you don't tell me the problem, I can't help fix it," says the doctor while looking at his watch.

Looking pale and vague, the slender boy points weakly to his lower abdomen. The doctor repositions him and begins to palpate. The cause of the boy's pain and bleeding appears to be the lower intestine. Assuming the child has irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), the doctor prescribes azulphadine. Case closed. Next patient.

Leaving the office, the boy's mother chastises him, "Why do I have to prod you to talk to the doctor? He's there to help you. You should be able to speak up for yourself!" The boy shrugs and looks away.

"Say something! Talk to me," begs the mother. She is concerned about her son's recent bouts with diarrhea and rectal bleeding, but also disturbed by his increasing distance from her and other people. Staring into the distance, the boy finally responds. "I miss Dad," he says simply.

Fast-forward 40 years. Rick is now a 46-year-old forensic accountant at a prestigious financial consulting firm. He has quietly built a career in the same company, examining the details of other people's business, looking into the intricacies of how they spend and make their money. As he analyzes each company, he finds meaning among endless spreadsheets that would baffle less careful and deliberate people. To him, each number tells a story and provides evidence to a larger plot. As a seasoned financial detective, he is accustomed to knowing much more than he is able to tell.

One day, business was not as usual. His department chief, a tall, well-dressed man, calls the meeting. A partner in the firm, he wields authority with ease. So, at his command, the accountants shuffle to the wood-paneled conference room and sit expectantly on high-backed leather chairs.

"Let's cut to the chase," says the partner. "I've called you all here to tell you that our company president has just signed a letter of agreement which sells us to..."

He then named the company's most hated competitor, a larger consulting firm known for competitive tactics that make sharks look like dolphins. Known for playing hard ball and questionable ethics, this "big fish" was about to eat Rick's smaller, yet reputable company. Thus is the case with mergers and acquisitions; in the waters of the free market, big fish win the hunt.

Along with trusted colleagues of many years, Rick felt nervous. He remained quiet as his manager described "the transition plan" that was to start that day. Plans called for Rick's department to be split up, and jobs offered to most, but not all of the current players. It was uncertain who the new leaders would be, or the exact location of the office, or the specific nature of the work, or for that matter, the level of compensation offered. A stable work environment that had taken years to create was about to be dismantled. Each accountant was now on his own and each case would be considered individually.

Rick felt a rumbling in his gut and imagined himself back on the doctor's examination table. All at once, the details of the conference room faded as he felt a sharp pain in his intestine. Though, in the present, he knew his manager was still talking, he couldn't hear the exact words. His mind blurred, and later that evening, he couldn't describe the details of the meeting to his wife. He felt inexplicably devastated by the events at work, though he was expected to arrive at work and continue to be productive.

"You look shell-shocked!" she exclaimed when he came home. "Tell me what happened. It can't be that bad. You'll have a job. You're great at what you do, and everyone trusts you. We'll be OK. Tell me, please."

Staring into space, Rick mumbles. Replacing his concerned mother with his wife, Alice now implores for contact. Once again, he is faced with unimaginable loss, and again his body is the bellwether of how he feels. Words don't tell his story. His intestine does.

Changes at work happen all the time. At the office, the rationale for change is usually quite reasonable. Profits must be made and decisions taken to promote corporate well-being. The values are clear and actions are taken to support them. It's rational. It's clear and not emotional.

But reaction to change is not rational at all. It is conditioned by how you've responded to change in the past, and how safe changes were historically. When Rick was six years old, his father suddenly left the family, starting a chain of events that left his mother depressed and overworked, leaving a child frequently without a functional parent to turn to. In Rick's unconscious mind, change is equated with loss.

The stress of his torn family took its toll on his intestines. Though there can be an organic basis to it, it is well-documented that IBS is always made worse by stress and is often caused by it.

As Rick quietly left the meeting (that was still in progress) and went to the bathroom, his body remembered an earlier loss, triggered by current events that cast a similar and enduring shadow on his life.

Later that day, his manager, a concerned man and a decent boss, came over to him. "Are you OK?" he inquired. "You looked pale at the meeting." Feelings washed over Rick, but he said nothing. His boss slapped him on the back, looked at his watch, and walked away. Would azulphadine manage this transition, too?

Reading this story, you may ask, what's the responsibility of organizations during times of change? What should leaders know in order to manage their organizations in a healthy way?

First, changes take energy, and energy is a finite resource. If you use more, you need to create ways to rebuild. During mergers and acquisitions (or any other times of major change), you can expect the ambiguity to drain some people. They will need personal and organizational ways that they can safely replenish. Second, your employees will respond differently to change. Those with traumatic reactions to change in the past will probably re-experience trauma, and will need help. And, finally, history repeats itself. And the body tells the story.