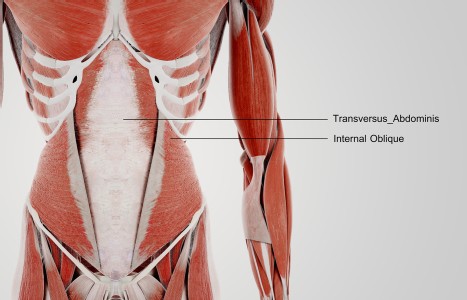

TrA-2, my primary needle location, I needle 95% of the time and I think it works the best. You’ll know you have the right point location when you discover the muscle twitching when applying electric stimulation.

The John Ritter Malpractice Trial: A Cautionary Tale

On Sept. 11, 2003, actor John Ritter died of an aortic dissection at St. Joseph Medical Center in Burbank, Calif. There is now a very large malpractice lawsuit against the hospital, the two medical doctors who evaluated him and various other personnel, brought forth by the Ritter family. How large is the lawsuit? The hospital and eight other medical personnel already have settled for $14 million. The two doctors remaining in the suit are being sued for $67 million.

Why are these doctors being sued? The allegation, according to the plaintiff's attorney, is that one doctor failed to warn Ritter of his enlarged aorta two years before he died. The other doctor, who was called to Ritter's side the night of his death, failed to order the proper tests to diagnose the condition. According to the attorney, because they didn't order the chest X-ray, they gave him the wrong treatment. They also are saying that if the X-ray were ordered, the actor would have undergone surgery that night and recovered in six to eight weeks.

What will happen with this case is unknown at the time of this writing. However, it illustrates potential problems that acupuncturists would do well to heed, regardless of the trial's outcome. Can we learn anything from this tragic story? My answer is a definite, "H@$$ yes."

I am a practicing chiropractor and I have been in practice for approximately 28 years in the Los Angeles area. Most acupuncturists know me for teaching the acupuncture orthopedics program, which I have done for almost 20 years. Although I am not an acupuncturist, I have been working with hundreds of licensed acupuncturists during that time. About half of the first module in the acupuncture orthopedics program deals with malpractice issues and how acupuncturists can do a better job of protecting themselves and their patients.

When you first see a potential patient, how good is your history? Do you just say, "Where does it hurt?" do a "quickie" exam and start treating? Do you ever obtain records of previous treating practitioners? Do you ever order copies of diagnostic imaging reports, lab findings, etc.? Do you rely solely on what the patient tells you or do you try to get independent sources to corroborate their complaints? Should you rely solely on what a medical doctor says and then just treat?

To me, there are two types of acupuncturists as determined by state laws. The first type requires referral by a medical doctor or similar health practitioner and the second type is allowed direct access without the need for a referral. Wherever you practice, you should read and know the laws that govern your practice in your state. Usually, these can be obtained free of charge by contacting your state licensing board.

Since I live and work in California and approximately 50 percent of all U.S. acupuncturists reside here, I'm going to discuss some California acupuncture laws. To begin with, you should know that if you are licensed in California, you have direct access to patients. As a matter of fact, according to the Business and Professions Code §4926, you are a "Primary Health Care Profession."

To me, this means you are responsible for working up a patient before providing care. You should be making educated decisions on whether this potential patient is someone you should treat or someone you should refer out. Sometimes (hopefully rarely), it may be an urgent situation that requires referral to an emergency room or calling 911. Other times, the situation may call for a referral to an expert specialist for a consult. After evaluating your patient, that specialist may send them back to you or may take other action.

While you may "lose" that patient, that's not what it's about. What this is about is serving the best needs of the patient, which should always be any practitioner's greatest duty.

How do you recognize what patients you should treat and which ones you should refer? There are many factors that go into this. Here are some:

- Take a thorough and complete history. This means listening to their chief complaint first. Find out if you are the first person they are seeing for this problem. If not, who have they seen before you? What was done? Were any tests ordered (e.g. X-ray, MRI)? Do they have a copy of any reports? If not, get their doctor's name, have the patient sign a release of records, and get copies of those records as soon as possible. What treatments were done? Did they make the patient better? Worse? No change? On a first visit, you also should do a systems review. This can be done on a simple form, but any abnormal findings should be reviewed by you with the patient. When the records arrive, review them and document that you reviewed them (one of the potential problems in the Ritter case).

- If you are the first practitioner seeing this problem, you may need some additional training. For example, if their chief complaint is a headache, would you know how to rule out a brain tumor? As a direct-access practitioner, you have a responsibility to figure this out. At the end of a history, you should have a pretty good impression of what is going on. This is known as your diagnostic impression.

- Perform a targeted examination. The exam is a way for you to verify your diagnostic impression. Global exams don't do that. Your history should be able to narrow things down for you. For example, is this a mechanical problem? Neurological? Pathological (e.g., tumor, arthritic process, infection)? The exam usually doesn't take that long because you mainly are doing the procedures you need to do to confirm or rule out your diagnostic impression. On the first visit, you should at least perform a vital-signs exam. This includes a patient's height, weight and blood pressure. Temperature should be taken if you suspect a condition related to abnormal temperature (e.g., infection).

- Determine a differential diagnosis. This means you need to come up with a potential "laundry list" of diagnoses. This may mean you want to rule out a potentially very serious problem (e.g., tumor) or you want to confirm that your diagnostic impression is following your history and exam. Sometimes you may need to order special tests, such as lab tests, X-rays, MRI, etc. and other times you may need to refer a patient to a specialist for a consult, such as a neurologist.

As an example, if a patient comes to you with serious low back pain and left leg pain, you may realize from your history that they have a pinched nerve. If you asked the right questions and did the right exam procedures, the combined information should tell you what level of spinal nerve you are looking at. You could diagnose a pinched nerve from that information (which might look like "radiculopathy" in Western terms). You would need to then determine what is pinching the nerve. Is it a herniated disc? A bone spur? A tumor? For that answer, you would need to order a special test or two.

With all of those results, you could then make the best decision for your patient: Do you treat them? Do you refer them out to a specialist? Do you do both and continue to work with the specialist? Here's a good question or two to think about: Do you think your patients assume that you know how to do all of this? What are their expectations of you?

If they read the brochure that the California Department of Consumer Affairs puts out called "A Consumer's Guide to Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine," they would assume you know how to do all of this. By the way, it's free to anyone who contacts the California Acupuncture Board. (Hint: perhaps you should read it - it's even downloadable from their Web site at www.acupuncture.ca.gov.)

In my opinion, when you are a direct-access practitioner, it is substandard to rely solely on a previous doctor's diagnosis. They aren't perfect and can often "miss the boat." Moreover, the other doctor is not responsible for your actions. I have heard several of my students say they were taught not to do a "Western" diagnosis. This is not only a ridiculous assertion in this day and age but it also can jeopardize your patient's safety by you not determining a condition you should be referring out. You can't expect a medical doctor or a patient to understand what "yin-deficient kidney" means when you make a referral. To refer, you need to "speak the language" and know what you are talking about to do the best you can for your patient. In future articles, I will discuss how to refer to and get referrals from other health practitioners.

Finally, document everything you do. In my experience, both as an educator and an expert witness in malpractice cases, acupuncturists get in the most trouble because of poor documentation.

If they are found guilty, the doctors in the Ritter case will face dire economic problems. I doubt their malpractice carriers will cover the $67 million, if that is the final amount the jury awards the Ritter family. Most of this revolves around the failure to diagnose and then make the proper decision - right or wrong. We can all learn from this and put the best practice procedures into our daily regimens for the good of our patients.