Because traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) views the human body as an interconnected network of energy (qi) and seeks to restore balance and harmony, ensuring the smooth flow of qi and blood is crucial to nourish and regulate the reproductive system. TCM treatment aims to regulate menstruation, reduce anovulatory menstruation, help ovulation, improve egg quality, stabilize progesterone, and provide a good endometrium environment for successful implantation and pregnancy.

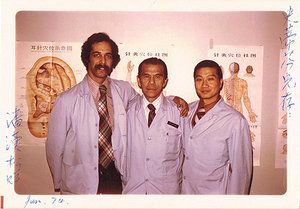

Steven Rosenblatt: Birthing A Cross-Cultural Acupuncture Profession

The existence of a cross-cultural acupuncture profession in the United States, one that is legalized, licensed, supported by formalized, academic training and inclusive of non-Asian practitioners, is an important part of the medical landscape in this country and is responsible for improving the lives of hundreds of thousands of Americans.

It is important to know the history and people who played pivotal roles in the development of the career you now call your own. Many of us contributed to the effort. But, Steven Rosenblatt MD, LAc, stands out as an initiator and innovator off of whose efforts the entire industry was built. This and my next article are to introduce you to him and the amazing work he did. He has broad shoulders and we all stand on them.

Steven Rosenblatt was a wild and passionate American kid who partied in Paris and hitchhiked to Pamplona, Spain to run with the bulls, during the summer of 1968, before starting graduate school. Once back to the states, he became a highly political, ambitious grad student in the psychology department at the University of California Los Angeles. His interests were pain perception and control. He and fellow students, David Bresler and Bill Prensky, ran animal lab experiments on how serotonin influenced pain perception and depression when this neurotransmitter was first discovered. They also brought unique interests, like Tai Chi, to the psyche department.

The boys studied Tai Chi at a park on Saturday mornings with Marshall Ho, whose studio was on the famous Sunset Strip in Los Angeles. For an upcoming Chinese New Year celebration, Marshall wanted some of his non-Chinese students to demonstrate Tai Chi in Chinatown so Steven and Bill obliged him. After the presentation, an elderly Chinese man walked up to the boys and said he had never seen white people doing Tai Chi before. This gentleman was a famous acupuncturist, they were told, and while neither Steve nor Bill knew what that meant, they didn't refuse the invitation to tea that followed.

Ju Gim Shek or Dr. Ju, became known as Dr. Kim to the boys, who thought the name Gim was pronounced Kim. He was a highly successful acupuncturist with a strong reputation in the Asian community. He was friendly and welcoming and began to cultivate a friendship with these unusual young men.

Dr. Kim was not from a lineage of doctors. Before he came to America he was trained by the Shaou-lin monastery monks. As a young man he lived outside the walls of the monastery and went in during the day. He was involved in many trading businesses in order to support his family, as his father died at an early age, thus, he could not become a full Shaou-lin monk. He was known as an outside- the- wall student.

Through his association with Steven he worked with his first causation patients. Steven became fascinated with acupuncture's effectiveness on pain and, over time, began to go to Chinatown every day to study. He was adopted into the community. "Every day we walked into China town's main street for a dim sum lunch. As we walked we practiced qi gong exercises for needle insertion. We became a recognizable site. A famous doctor and his "Lo-fan" (white) son," Steven said.

Dr. Kim's own son wasn't interested in becoming an acupuncturist. He wanted to be an "American." So Steven assumed a unique role in Dr Kim's life. "I was in charge of sterilizing and preparing needles for each patient. There were no disposables then. And I ran with Dr Kim's prescriptions to the pharmacy on Spring Street so they could be filled as paper wrapped packages of crude herbs. In the beginning, I worked with moxa on needles. I wasn't allowed to do needle insertion until I was more skilled," he said. Steven's skills improved for the three years, from 1969-71, that he apprenticed under Dr. Kim.

Dr. Kim decided he wanted to teach on a larger level, formalizing what he knew into a didactic method. David, Steven and Bill helped him put a class together at Marshall Ho's Tai Chi studio. There were eight students. The class went on twice-weekly for a year. There was a second class the following year. By the time both classes were complete, these ambitious and politically driven young people considered themselves practitioners of acupuncture and were pondering how to get it licensed.

After three years, Dr. Kim felt Steven should continue his education beyond what he had to offer. He flew with Steven and his girlfriend Kathleen, to Hong Kong to introduce them to his colleague, Dr. James Tim Yau So. With great ceremony, Dr. Kim formally handed his students to Dr. So who, since 1939, had run the Hong Kong Acupuncture college and clinic. Dr. So spoke English well because Hong Kong was British. Still, these young Americans were the first Westerners anyone had seen. They didn't learn Chinese during the three months they were there because everyone wanted to speak English with the Americans.

They became close to Dr. So and spent time at his home. Dr. So confided that he had always wanted to go to the U.S. and had hoped to live out the rest of his life there. It was 1972 and President Richard Nixon had gone to China. Acupuncture was being talked about everywhere because one of Nixon's press staff, James Reston, had an emergency appendectomy with post-operative acupuncture to address pain when he was in Beijing the summer before Nixon's trip. Reston wrote an article on the experience for the New York Times. That was a big break for our field. When he got back to UCLA, Steve, ever the political animal, did lots of PR on the subject and on himself as a practitioner and student of the Hong Kong college.

Steven convinced the anesthesiology department at UCLA medical school to sponsor an acupuncture clinic to investigate its effects on pain. Gordon Duffy, a California state assembly member, worked with Steven, David and Bill, to pass a California bill that allowed acupuncture to be done in a medical school under a physicians' supervision. The law was passed. Steve became the clinical director as well as a practitioner.

Dr. So came to this country with a "distinguished person's" visa, to work in the clinic, which was located at UCLA hospital. He was welcomed as a man who had run a medical college for 35 years. The clinic was a smashing success with constant waiting list and people lined up out the door waiting to receive acupuncture for chronic pain. Steven said "the clinic was actively supervised by several different MDs., especially Vern Brechner, MD, and Teresa Frerrar, MD. The chairman of the department was Ron Katz, MD who was a tremendous help and advisor in getting this groundbreaking clinic up and running. This was the first acupuncture clinic in a medical school in the U.S."

Dr. Kim, Steven's first teacher in Chinatown, was invited to work with the clinic, but because acupuncture was now on everybody's radar and had no formal licensure, this great doctor who had maintained a thriving practice in the Los Angeles Chinatown community for a lifetime, was arrested for practicing medicine without a license. Charges were later dismissed but Dr. Kim lost his spirit to work at UCLA.

After the clinic had been running a year and a half, Steven and Dr. So received an offer to start clinics in Boston's Kenmore Square and in Worchester, Massachusetts. Up for adventure, they headed East. Unfortunately, neither clinic went well for several reasons. They had moved into a conservative area, a seat of great Western medical studies, and they were not at a university medical school. These were private clinics depending upon personal sponsorship or patients who could afford to pay sufficiently for their care. After the original backers dropped out they were forced to close. But good things were to come.

An MD who had been studying with them asked if they would come treat in his clinic in Brookline, which they did. Dr. So also wanted to teach Westerners, so Steven helped him organize his educational material the old-fashioned way. Dr. So would dictate and Steven would write everything he said down by hand. These thick, hand scrawled notebooks were, years later, published by Redwing Books as A Complete Course in Acupuncture by Dr James Tin Yao So. After extensive revisions, the text was converted into a two volume set and re-titled The Book of Acupuncture Points and Treatment of Disease of Acupuncture. It is great work, the cornerstone of Dr. So's teachings, and is still available from Redwing Books.

The James Steven Acupuncture Center, named for both Dr. James So and Steven Rosenblatt, was located in a Tai Chi studio that Steve had opened and at which he taught, in the East End of Boston. Daytime was spent in the MD's clinic, treating and evening found them teaching in Steven's one room Tai Chi studio.

You may have heard of this esteemed institution by a name it later acquired - The New England School of Acupuncture. This humble, single room in East Boston is the first incarnation of one of our great schools in the U.S. And the hand-written notes that an eager, young grad student wrote while listening carefully to his teacher, ultimately became NESA's primary textbook. The first class in the little studio had more than 20 students, many of whom have continued to practice and have had substantial impact on our profession over the past several decades.

Steven is responsible for doing much more for our profession: writing the first PhD dissertation on acupuncture in the U.S., conceiving of and working for licensure in the first states ever to agree to it, opening more schools and instituting accreditation standards for colleges. I shall share more with you of his endeavors and of the birthing of our profession in the second part of this article next month in Acupuncture Today.