The most important relationship I seek to nurture in the treatment room is the one a patient has with their own body. We live in a culture that teaches us to override pain, defer to outside authority, and push through discomfort. Patients often arrive hoping I can “fix” them, but the truth is, we can’t do the work for them. We can offer guidance, insight and support, but healing requires their full participation.

Decreasing Opioid Prescriptions With Acupuncture at a Federally Qualified Healthcare Center

Acupuncture is being increasingly offered to patients as an alternative to opioid prescriptive medications for the treatment of pain. However, to date, there has been little published evidence available to demonstrate whether opioid prescriptions are decreasing as a result of acupuncture use.

Research does show that acupuncture improves pain levels in adults. Systematic reviews support the effectiveness of acupuncture for acute and chronic low back pain.1-2 Licensed acupuncturists treat a number of types of musculoskeletal and internal organ pain, such as arthritis, tension and migraine headaches, dysmenorrhea, nervous systems disorders, and irritable bowel syndrome. Thus, there is ample evidence that acupuncture can be effective for a number of pain disorders.3

Acupuncture at FQHCs: Challenges and Opportunities

The use of acupuncture in low-income urban health care settings also is gaining acceptance, although there are a number of barriers to its provision at Federally Qualified Healthcare Centers. Barriers include the lack of coverage for acupuncture treatments by licensed acupuncturists in the Medicaid plans of most states; lack of credentialing standards for licensed acupuncturists at FQHCs; and the need to increase awareness of the effectiveness of acupuncture in both the patient and primary care clinician populations.4-6 Despite these obstacles, the availability of acupuncture in urban settings continues to grow as the number of licensed acupuncturists increases.

As mentioned, to date there has been little direct evidence that the availability of acupuncture as a treatment for chronic pain has reduced opioid use. In one retrospective review in a military setting, the number of opioid prescriptions was shown to decrease when acupuncture was available as a therapy.7

The Bridgeport Example

The University of Bridgeport Acupuncture Institute (UBAI) provides acupuncture and other traditional Chinese medicine treatments two half-days a week (eight hours per week) at a local FQHC in Bridgeport Conn., the largest city in the state. The acupuncture and related services are provided without charge to FQHC patients referred for acupuncture by their primary care physician. Acupuncture, moxibustion, cupping, gua sha and tuina are provided by UBAI student interns under supervision of licensed acupuncturists who are credentialed with the FQHC.

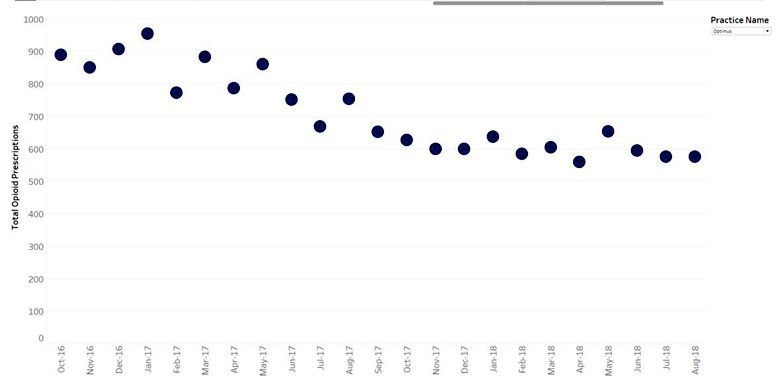

The FQHC staff reviewed numbers of opioid prescriptions immediately before and during the months after the introduction of acupuncture as a treatment option, to identify the outcomes effectiveness for acupuncture in this setting.

Results and Discussion

As seen in the graph, the number of opiate prescriptions written at this urban FQHC has decreased steadily since the introduction of acupuncture in January 2017.This evidence suggests offering acupuncture as an optional treatment for pain can help reduce opioid pain medication prescriptions in an urban FQHC setting. (Whether the same outcomes would be identified if the FQHC patient population were required to pay out of pocket for the acupuncture treatments is unknown.)

Additional acupuncturists credentialed and privileged at the FQHC to allow six-day a week availability and a method of paying for the care in such a setting is needed if TCM is to have a significant impact on the opioid crisis at this Bridgeport FQHC, much less at similar facilities across the U.S.. In addition, if acupuncture services were covered under Connecticut Medicaid plans, the number of FQHC settings offering acupuncture would likely increase significantly and a similar decline in prescriptions for opioid medications might occur.

References

- Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly J, et al. Nonpharmacologic therapies for low back pain: a systematic review for an American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med, 2017 Apr 4;166(7):493-505.

- Furlan AD, Yazdi F, Tsertvadze A, et al. Complementary and alternative therapies for back pain II. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep), 2010 Oct;(194):1-764.

- Skelly AC, Chou R, Dettori JR, et al. Noninvasive Nonpharmacological Treatment for Chronic Pain: A Systematic Review [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2018 Jun. (Comparative Effectiveness Review, No. 209.)

- McKee MD, Kligler B, Fletcher J, et al. Outcomes of acupuncture for chronic pain in urban primary care. J Am Board Fam Med, 2013;26(6):692-700.

- McKee MD, Kligler B, Blank AE, et al. The ADDOPT study (Acupuncture to Decrease Disparities in Outcomes of Pain Treatment): feasibility of offering acupuncture in the community health center setting. J Altern Complement Med, 2012;18(9):839-843.

- Kligler B, Buonora M, Gabison J, et al. "I felt like it was God’s hands putting the needles in": a qualitative analysis of the experience of acupuncture for chronic pain in a low-income, ethnically diverse, and medically underserved patient population. J Altern Complement Med, 2015;21(11):713-719.

- Crawford P, Pensien DB, Coeytaux R. Reduction in Pain Medication prescriptions and Self-reported Outcomes Associated with Acupuncture in a Military Patient Population. Med Acupuncture, Aug 2017.